John Carpay, The Epoch Times, December 2, 2019

Can children in public schools be subjected to spiritual practices or ceremonies that invoke the supernatural? Are some practices religious even while also being cultural?

These are among the questions the B.C. Supreme Court will wrestle with after hearing the case of Candice Servatius v. School District No. 70 (Alberni).

The case originated in September 2015, when Candice Servatius received a letter from the principal of John Howitt Elementary School in Port Alberni, British Columbia. The letter stated that the school would be hosting a “cleansing” of students and the classroom, performed by a member of the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nation of Vancouver Island.

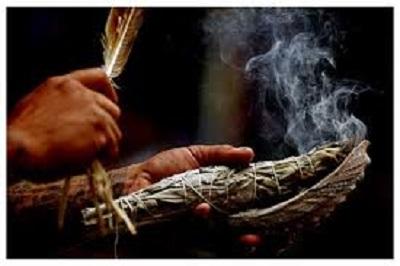

The letter to parents described in detail how smudging, a spiritual ceremony using smoke from burning sage, would “cleanse” the classroom of bad “energy” and cleanse the “spirits” of the students. The letter claimed that without cleansing, the classroom and even the furniture would harbour negative “energy,” and implied it would not be safe until the “energy” was “released.” It also described Nuu-chah-nulth spiritual belief that “everything has a spirit” and “everything is one, all is connected.” There was no opt-out provision in the letter. At least one of the teachers didn’t even bother to send it home to parents at all, testifying later in court that parental consent wasn’t required.

Without the knowledge or consent of Servatius, who has two children in the school, smoke from burning sage was fanned over the walls and furniture of her children’s classrooms, also reaching all the children in the classroom. Servatius’s daughter has testified that she was required to be present against her will. Several months later, an aboriginal prayer was offered to a “god” at a school assembly that children were required to attend.

Canadian courts have ruled decisively against public schools requiring children to recite the Christian prayer known as the Lord’s Prayer. Religious freedom means the right to practice one’s faith and also the right not to have a religion or religious practice imposed. Courts have ruled that requiring children to pray amounts to imposing a religious exercise, contrary to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Courts have also rejected the proposal of protecting religious freedom by exempting the children of atheists, Jews, and other non-Christians from saying the Lord’s Prayer. For a child to make use of the exemption would effectively force that child to express his or her unwillingness to say the Lord’s Prayer. The courts ruled that no child should be required to announce a non-belief in Christianity, as doing so could result in stigma or ostracism. A person has the right not to disclose his or her religious belief or non-belief to other people.

In response to these prior court precedents about the Lord’s Prayer, the Alberni School District argued that no religious practice was imposed on Servatius’s daughter. The district claims that the daughter, then 9 years old, was merely present in the smoke-filled classroom, and did not have sage smoke waved over her individually.

However, according to the liaison for the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council who was present, the cleansing was held specifically for the purpose of removing energy from a known incident of bullying in one classroom, and a case of personal injury in another. This bad energy exists in the unseen world and is removed by a cleansing ritual, said the witness, who confirmed that the walls and doors were cleansed by sage smoke, as well as the space of the classroom itself.

The Servatius family argued that being mandated to breathe in and be touched by spiritual smoke for spiritual purposes amounts to forced participation in a spiritual ceremony.

What would the reaction be if a Catholic or Orthodox priest had blessed their child’s classroom through prayers and by the sprinkling of holy water on the walls, desks, and children?

The school district also argued that the smudging cleansing ceremony is cultural, not religious. The intervenor Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council asserted that aboriginal spirituality is not religion, and that aboriginal languages have no word for “religion.” This argument has been rejected by the Supreme Court of Canada, which ruled in Ktunaxa Nation v. British Columbia (Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations) that aboriginal spiritual beliefs qualify as “religion” for the purposes of being protected by section 2(a) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The Servatius family does not object to learning about aboriginal culture. They object to compelled participation in a supernatural or spiritual ceremony.

One of the witnesses in the court action was Harry Cadwallader, the former director of the Aboriginal Education Enhancement Branch within B.C.’s Ministry of Education. He testified that learning about smudging is different than being smudged. He agreed that children can learn about smudging in a number of different ways: “You can be shown a demonstration. You can be shown a video. You can be read a description,” he said.

Cadwallader testified that “the infusion of aboriginal culture, content, language, history, of understanding, as a methodology to improve the success of aboriginal students and raise awareness of all students about aboriginal people” can be accomplished without compelling children to be smudged against their will.

The CBC and some other media have blatantly mischaracterized the Servatius court action as an attempt to remove aboriginal content from the B.C. school curriculum. But in fact, if Servatius is successful, public schools will continue to teach about Nuu-chah-nulth culture, including spiritual beliefs. The Nuu-chah-nulth will also still be able to provide spiritual ceremonies as optional exercises during non-mandatory class times. Freedom of conscience and religion will be maintained as required by the Charter, and both parents and students will be able to be non-participants in accordance with their own personal beliefs.

This is what the law requires.

Lawyer John Carpay is president of the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms (JCCF.ca), which represents Candice Servatius in her court action against School District 70.